Vangelis’ film score for Blade Runner

Since the introduction of sound-on-film in the 1930s, science fiction film-makers sought to harness the new medium of sound to emphasise outlandish atmospheres and give the audience an out-of-this-world auditory experience. In the 1950s, during Hollywood’s Golden Age of Science Fiction, films witnessed an increased use of electronic sounds for contextualising unfamiliar worlds to film viewers. Instruments such as the theremin and the ondes Martenot, with their eerie sounds, were used to great effect, while other new sounds were created using a variety of other electronic instruments, such as the Hammond Novachord vacuum-tube synthesiser, or by employing studio methods to transform existing sounds into new ones.

The 1956 thriller Forbidden Planet, directed by Fred M Wilcox, featured a pioneering musical score created entirely on handmade electronic circuits by sound experimentalists Louis and Bebe Barron. The soundtrack is famous for introducing a new approach to the creation of a film score, as its sound effects were created entirely electronically, without any use of traditional instruments.

With the invention of the analogue synthesiser in the late 1960s, a handful of dedicated musicians and composers embraced the new instrument, and they incorporated it in their work. In Stanley Kubrick’s 1971 film A Clockwork Orange, a modular analogue synthesiser was used by composer Wendy Carlos to recreate lush electronic versions of well-known classical pieces. At this stage, the new analogue synthesiser was difficult to set up and required technical skill to produce the desired sound, but its introduction ushered a new dawn for musicians who were eager to learn how to tap into a keyboard instrument with new sources of sound.

As analogue synthesisers developed, they entered different genres of music, and in the 1980s, with the introduction of cheaper and simpler models, they became even more widespread in popular music. Many old-school composers and music conservatives at the time believed that the use of synthesisers distanced the music performer from direct contact with the musical instrument, and they argued that, when used in film scores, the new electronic instruments could never capture the same level of warmth and emotion as when a score is written for a symphony orchestra, or when played directly by a musician on their instrument.

In 1982, Vangelis’ synthesiser-based film score to Hugh Hudson’s Chariots of Fire won an Academy Award for best original score, strengthening the new synthesiser trend and its potential. Electronic film scores no longer needed to be confined to recreate electronic realisations of classical music or provide pastiche sounds to describe bizarre aural narratives. The score to Chariots of Fire, with its classically trended style, incorporated grand anthems and uplifting melodies, engaging the public with the film’s heroic message.

So when film director Ridley Scott asked Vangelis to write the score to his upcoming film Blade Runner, contrary to public belief, the use of electronic music was not a deliberate attempt by Vangelis to copy commonly used ideas and sounds as seen in science fiction films. Electronic music was already part of Vangelis’ everyday musical language, and he performed using synthesisers because these instruments allowed him to spontaneously create symphonic works without the aid of session musicians.

Probably one of the less noticeable aspects of what adds to Blade Runner’s extraordinary score is Vangelis’ instinctive way of capturing the subtle visual cues from film and embodying them in a seamless music score. As we gaze at the ‘Spinner’ car flying above the city’s panoramic landscape there is a sense of levitation in the music, endowing the aerodyne vehicle with a cause and effect within the musical score. Architectural and technological objects in Blade Runner also produce sounds and suggest they are part of the film’s sonic landscape. When the huge polarising windows at Tyerll’s office begin to reduce the amount of daylight into the room, the effect is complemented by musical drones that are wholly integrated into the music.

The prelude music to the love theme between Rick Deckard and Rachael Tyrell is an example of Vangelis’ mastery of expressing his instantaneous reactions as the scene is unravelled. Vangelis uses electronic music to amplify the emotions that are felt inside Deckard’s apartment, and we notice there is an emotional tug between Vangelis’ music and the two characters. The music changes in intensity as it progresses, from being apprehensive and doubtful to confident, as Rachael and Deckard confront their emotions and fears. The music concludes with sultry saxophone music which signals to the audience that this is the film’s love theme, and any questions of apprehension between Rachael and Deckard are now overcome by recognisable human emotions. The music is played straight from Vangelis’ hands to the recording tape and interacts and responds to the characters and the moods right inside the room.

The penultimate scene in Blade Runner shows how crucial Vangelis’ music is in providing the film viewer with an emotional response, which would have been difficult to portray without the use of music. The scene involves Deckard’s assumed enemy, Batty, who is being chased by Deckard in the pouring rain on the roof of a building. As Batty realises his aspirations to extend his life are dashed and his time is drawing near, in a moment of pitiful irony, he saves Deckard from impending death. Rather than letting the viewer hear music trumpeting the end of Batty, it unexpectedly joins him on his sad end as he grasps for his last moments. We also see Batty’s hands holding on to a dove that he found on the roof of the building. As Batty lets go of life his grip on the dove loosens; and Vangelis punctuates this poignant moment as the dove’s wings flutter and it tries to set itself free from the clutch of its captor. The dramatic sonic moment is shown in slow motion, but it almost goes by unnoticed by the viewer. This musical movement emphasises the transition between life and death, between captivity and release. The music then changes in an instant, from a lullaby into a grieving and an almost heroic theme, clearly dedicated to Batty, a replicant that perhaps, in the end, showed more human traits than most actual humans.

But there is a twist in Vangelis’ music, just as the characters Rachael and Deckard question whether they are of human origin or are in fact replicant clones. There is something about Vangelis’ music that mirrors this duality of origin, unintended as it may be. Unlike other science fiction films that often relied on outlandish electronic sounds to suggest stories that are set in an unfamiliar and alien world, Vangelis’ choice of sounds for the Blade Runner soundtrack evoke a sense of familiar-sounding instruments.

Among the musical instruments we hear ductile bending horns, electrical streaks of violin strings, shape-shifting brass, mechanised Far Eastern harps, brittle and metallic pianos and eerily deformed bells. These new electronically created sounds are perhaps yearning to a bygone past – perhaps these sounds come from ‘replicant’ musical instruments that were cloned to sound like traditional instruments, or perhaps they were designed to surpass the capabilities of the instruments they were derived from?

Vangelis achieved this by embodying our current day knowledge (or memory) of well-known instruments, but modified their sounds electronically, as if they were instruments from the not-too-distant future.

Vangelis’ views on scoring for films

Vangelis distinguishes between the approach he follows when he creates music as compositions in their own right to his duties as a film score composer. When he creates music on any ordinary day Vangelis does not conceptualise images or thoughts while he is actually carrying out the creative process, nor does he know what the composition will be like.

For Vangelis, music is a natural creation, and, therefore, music cannot be created as a consequence of past or active human thoughts. Only after Vangelis finishes recording a composition and listens back to his music does it induce ideas, and he can then analyse what he has just recorded on tape.

Approaching music for film is different, as Vangelis views his role, first and foremost, as serving the film, and films, by their nature, involve moving images. Vangelis’ music is not created through a rigorous process where compositions and musical motifs are methodically thought out and arrangements are carefully laid out. He also never reads a film’s script, to avoid the risk of creating a version of the film in his head that might deviate from what the film director intended.

Instead, he waits to see what the film director proposes visually, on film, and afterwards he joins in as a participant and, through his music, interprets what the images might not have been able to say on their own. Vangelis tries to capture his first impression of the visual images as he plays, letting his spontaneity react to the images and not letting his thoughts interfere with his inspiration.

To Vangelis, the acts of composing and performing are indistinguishable from each other, so any attempts to analyse the melodies are completely avoided. So, in this sense, to answer critics who question the use of synthesisers in films, instead of a music performer being in less direct contact with the musical instrument, Vangelis used synthesisers to achieve a more direct relationship with the instruments – as a composer. He could perform a symphonic composition – almost in its entirety – in one single setting.

Vangelis believes that trying to reason how ‘creation’ works is futile and can interfere with the creation process itself. Vangelis sees his method of composing as like a child riding a bicycle: if the child asks how the bicycle moves forward the child may fall off the bicycle as he/she tries to rationalise his/her movements. By not dwelling on creation, Vangelis aimed to keep his approach pure – it is best not to think and just play.

The recording studio’s equipment

Vangelis’ studio consisted of a control room and a live room. The control room was equipped with a multitrack tape facility that allowed the recording of musical instruments into audio tracks on analogue magnetic tape, and these audio tracks could then be mixed down onto a master tape.

The control room not only contained the tape recorder machines and the mixing desk, but, it also served as the area where Vangelis composed music on his synthesisers. The control room was like an extension of his instruments, the sound processors, the outboard equipment, the tape machines and the mixing desk, all of which played a part in Vangelis’ performance.

An adjacent live room was filled with traditional instruments and other unusual musical items Vangelis had collected over the years. It also featured a wide collection of percussion, which included drums, gamelan, timpani, tubular bells, gongs and orchestral percussion. The live room was often used as the area where live work was recorded, which also included guest singers and other musicians.

Vangelis’ studio featured commercially available models of synthesisers as well as some old vintage electric keyboards, and it also had a 9-foot Steinway Grand Piano. All of these instruments were situated in the studio’s control room next to the tape recorders.

The control room was equipped with two types of tape machines, each dedicated to a certain function in the recording process. The first was a multitrack tape machine capable of recording 24 parallel audio tracks into a 2-inch-wide magnetic tape. The multitrack tape allowed the individual instruments from a performance to be recorded into discrete audio tracks. This gave flexibility during mixing, as each audio element could be treated separately for panning, gain or other fine-tuning. Vangelis’ multitrack tape machine was the Lyrec TR-532, the same tape machine he used to record his solo albums and his film score to Chariots of Fire.

The second type of tape machine in Vangelis’ control room was a ‘tape master’ machine that allowed the final mixed work to be produced onto a 2-track quarter-inch master tape. Blade Runner was going to be presented in cinemas with Dolby Stereo sound and using a 4-channel mix of the soundtrack. A 4-track master tape machine was rented so that any music mixes needing 4-channel mixes could be delivered on a 4-track tape.

Vangelis’ studio central command was a mixing desk – a 36 channel from Quad/Eight Electronics ‘Pacifica’ multitrack non-automated mixing desk configured as a 36-modular input console with eight selectable mixing busses and stereo mix down. Two separate stereo (cue) busses and four auxiliary send circuits (i.e. four echo send/return module) per channel input.

For audio monitoring, Vangelis’ studio was equipped with two Tannoy Dreadnought monitors capable of delivering 750-watt. Each monitor was equipped with dedicated Tannoy cones for high-, middle- and low-frequency ranges, and each range was powered by a dedicated amplifier, using three BWG 750-watt amplifiers.

When recording a track of audio onto analogue tape, the audio is accompanied by the presence of tape hiss noise due to the limitation of the magnetic medium. When working with multitrack audio tapes, the amount of tape hiss noise stemming from all 24 tracks can be noticeable, especially when the audio recording changes to quiet passages of music. This build-up of unwanted tape noise was dealt with by the use of a noise-reduction system. To reduce tape hiss Vangelis used dbx noise reduction Type I, by applying it to each of the 24 tracks of the Lyrec TR-532 tape machine.

Tape hiss noise on 2- and 4-track master tapes was addressed by applying another type of noise reduction. For the Blade Runner soundtrack, these were handled by noise-reduction modules installed by Dolby Laboratories for the master tapes. The Dolby noise reduction was applied on each of the 2 or 4 channels, depending on the number of channels used on the track in question. Occasional audio peak limiting was provided by URei 1176-LN compressors.

While creating music in a multitrack tape studio environment offered immense opportunities for adjustig the recorded performance, it lacked many of the convenient tools that arrived with later technologies, such as mixing desk automation, SMPTE time-code for synchronisation and much of the digital facilities that swept the sound-recording and film production studios in the late 1980s and beyond.

A reconstructed overhead view of Vangelis’ studio in 1982

You can view a number of photographs of the studio by clicking on any the numbers indicated on the surface of the map. Tap on the photo or hit the esc key to close down the pop-up photo. All of the photographs were taken in 1982 during or shortly after the making of the Blade Runner film score.

When writing the score for a film Vangelis would view the picture from a screen positioned at location TV no. 1. The studio assistant would view the picture on a television screen typically placed on the piano at TV no. 2. For added convenience sometimes a television screen was also placed at TV no. 3.

Synthesisers

The long notes in the film’s opening credits were created on Vangelis’ Yamaha CS-80 synthesiser, an instrument that featured many performance controls, including a ribbon controller that gave Vangelis the flexibility apply a pitch bend to his notes. It also had polyphonic aftertouch, which gave Vangelis control over each note’s inflection and modulation by varying the amount of pressure on each key pressed on the instrument.

Besides the Yamaha CS-80, two other prominent instruments heard throughout Blade Runner are a Roland VP-330 VocoderPlus synthesiser, for the string section, and a Fender Rhodes, for the nostalgic-sounding electric piano.

Other instruments included a Sequential Circuits’ Prophet 10 synthesiser, used for producing low drones and effects, E-Mu’s Emulator keyboard, put to use as a percussive sampler and a sound library, and Yamaha GS-1 for occasional percussion effects.

Vangelis created the enormous spatial distance of the score by running his instruments through a Lexicon 224 digital reverberation sound processor. He used it by applying depths and spaces to his synthesisers and percussion, creating lush spaces to complement the film’s vast landscapes.

For compositions that incorporated the occasional use of pulsating sequencer work, Vangelis had a set-up consisting of several Roland synthesisers and sequencers. This allowed him, during his performance, to adjust, transpose and edit the sequence as he played along. The Roland synthesisers included the Jupiter 4 and the ProMars CompuPhonic, and the Roland sequencers included the CSQ-600, CSQ-100 and System-104.

Recording the score, London, 1982

After the completion of Blade Runner’s principal filming in Los Angeles, in the summer of 1981, the film’s post-production phase moved to London, where it was to be assembled and sound dubbed. Film director Ridley Scott, along with his film-editor Terry Rawlings, began to put together a rough cut of the film. Rawlings began to use a temp score to put music to the images. The rough cut of the film with the temp score gave a flavour of the type of mood Scott might have wanted, and allowed them to view an assembled film put together from all the cut scenes in chronological order.

Vangelis was approached to discuss the possibility of providing the film score for Blade Runner and was invited to a private view of the film on a cinema screen at Pinewood Studios. In December 1981, after fruitful discussions, Vangelis was signed up to work on the film.

Blade Runner was not the first collaboration between Ridley Scott and Vangelis. They had worked together a couple of years earlier, in 1979, when Scott commissioned Vangelis to rework a piece of music for one of his commercials, the iconic fragrance Chanel N°5, entitled ‘Share the Fantasy’.

Vangelis’ studio in London was his own privately funded and operated recording studio, which contained over a million pounds worth of equipment and instruments. The studio had one member of staff who worked as a studio engineer and, among her tasks, she supervised the operation of the tape machines, helped Vangelis with various mixing desk duties and synchronised tape recording to video playback.

Vangelis’ home base in London and its proximity to the film editing studios was very convenient, as it allowed filmed scenes to be quickly dispatched to Vangelis and, likewise, Vangelis was able to deliver his music to the dub theatre.

In anticipation of recording Vangelis’ score in Dolby Stereo, consultants from Dolby Laboratories visited Vangelis’ studio and checked the compatibility of his studio’s equipment. The consultants also installed Dolby noise-reduction units for putting the 4-track mixes onto quarter-inch tape.

Vangelis received the filmed scenes from Blade Runner’s editing room on a day-by-day basis. Vangelis received these cut scenes on video cassettes in Video Home System (VHS) format and the video streams contained the dialogues from the actors and nothing else. Any temp music used in the rough cut was removed. There was also no information in the video streams, such as time-code readout, to assist the film editor or the musician aligning the music to the film throughout the various stages of music and film editing.

When composing and recording music for a soundtrack, Vangelis utilised the control room of his studio by using a television screen to view the cut scene he was working on. Situated behind the television screen, Vangelis was surrounded by a dozen synthesisers. Additional television screens were also placed at different corners in the studio, so Vangelis could see the film from any position while he worked. Synchronising the video playback and the tape recorder was carried out by remote control. This meant pressing play on the videotape and pressing the record button on the tape machine at the same time.

As a new filmed scene was played, and if Vangelis felt a strong connection to the moving images, he would create a composition straight away. Being lead by the moving pictures, he would record his creations without any prior rehearsals. Otherwise, if viewing the film scene induced no immediate reaction, Vangelis would not push himself to force the music out, instead he would work on some other tasks at the studio and come back to it later on.

If Vangelis felt that a composition needed additional layering, he would rewind the tape and add layers of sound electronically, through his synthesisers, percussion and acoustic effects. The number of overdubs could be kept to a bare minimum, to avoid turning his music sick by tampering with it beyond what was necessary. Vangelis always prefers to use his first take whenever he can, even if the recording contains small mistakes, because he sees his first takes as more honest than rerecording the same music again.

Sometimes, certain subsequent overdubs required precise timing with the film cut, as it was important to maintain synchronisation between tape and video. However, there were no electronic editing facilities available at the time to allow recording new inserted audio elements starting from a predetermined video frame. Synchronisation was carried out by hand and done by operating both tape and video machines manually. The tape would be rewound to the start of the recording segment using the tape-counter readout, or if working on a subsection of tape a line would be drawn on the non-magnetic base of the tape with a chinagraph pencil to indicate the position of music. Similarly, the VHS videotape would be rewound to a previously chosen video frame as a reference point by using the pause function on the remote control.

Once both machines were in standby mode the record button would then be pressed on the tape machine and then, after counting to 10, the play button on the videotape player would be activated. This would mean that Vangelis could watch the video in sync while adding the new layers of sound.

Since this type of manual synchronisation was never consistent on every subsequent overdub, this meant that with each successive viewing there was the possibility of a slight misalignment between audio and video. The studio engineer operating both machines ensured the alignment was as accurate as possible. The synchronisation may be described as loose today, but it was part of Vangelis’ creativity in making organic music without using a click-track for synchronisation.

With some of the compositions, Vangelis felt that he wanted to redo certain arrangements using a vocal performer, a choir or a traditional instrument, such as a saxophone. On those occasions, a studio session would be arranged for an invited singer or a musician to rehearse and record the part Vangelis needed to achieve, and these new elements would then be added to the multitrack tape.

After the composition was recorded, with any overdubs, the recorded arrangements would then mixed down and put onto a master tape. Vangelis viewed the mixing desk as a conductor of all other instruments. He would sit in the engineer’s chair, in the centre of the mixing desk, moving sliders, twiddling knobs and pushing buttons. Standing next to him would be the studio assistant, who would make any other necessary adjustments.

The studio was exclusively used for stereo recordings, and the mix for the Blade Runner soundtrack was the first 4-channel mix ever attempted at Vangelis’ studio. The mixing desk, for example, had no built-in panning options for surround sound. The procedure was further lengthened by the lack of an automated mixing desk, as it required manual human input for manipulating (in real time) 24 audio channels coming from the multitrack tape machine. So every attempt at mixing a track required active human involvement in monitoring and adjusting each of the 24 tracks on the mixing desk, by adjusting gains, filtering and panning.

For jobs requiring 4-track mixes, rather than relying on the mixing desk’s built-in stereo busses, the channels were instead re-routed to their auxiliary subgroups and combined into a 4-channel submix. Panning a sound across one of the four submix channels had to be manually tuned and monitored by listening to the mix on the four monitors in the control room. For simplicity, the 4-channel mix was approached as a normal stereo project with occasional effects panning from left – centre – right and surround. Sometimes a sound effect would be placed at the surround channel; as such sounds had little influence on the composition as a whole.

Much of the aural sound used in Blade Runner’s soundtrack was simple. The synthesisers were patched on the individual channels on the mixing desk, a portion of the signals from the channels were sent to the auxiliary send circuits which went to the Lexicon 224 reverb and returned on the channel returns further up the mixing desk and mixed into the designated buss group. The Lexicon reverb was applied live as the multitrack tape was played back, and it was never recorded in the original audio stems on the multitrack tape.

Several attempts at mixing would have to be tested and tried, until the final execution and the desired mix was achieved without any errors. Since the mixing jobs could not be saved for later retrieval, every adjustment had to be manually redone in real time. The mix practices may be repeated as many times as necessary, with every new mix practice being an improvement on the previous attempt, until Vangelis was satisfied with the results and the final master tape was produced.

Another minor technical issue to address was the fact that the filmed scenes sent to Vangelis’ studio were delivered on VHS videotapes. Because videotapes were transferred from an optical motion picture into a standard UK PAL video signal with a Telecine machine, this presented a problem, where source and target video formats ran at different frame rates. The video stream of a PAL UK standard ran at 25 frames per second (fps), whereas optical film is produced at 24 fps on 35-mm film. It meant that the cut scene from Blade Runner at Vangelis’ studio played at the slightly faster, 25/24, rate. This presented a speed synchronisation problem between what Vangelis’ played to and how the music was synchronised to the final optical film at 24 fps.

In order for Vangelis’ film score to sync to the optical 24-fps film, the music was initially composed to synchronise with the VHS videotape, at 25 fps, and when the track was completed it was then transferred to the master tape and sped up by a factor of 25/24, using the variable-speed function on the tape machine. This correction step prevented the possibility of the film score drifting and losing sync with the film.

Vangelis composing on his synthesisers while looking at a film scene displayed on a video screen, which was located behind the mixing desk in front of him. The television screen on top of the grand piano behind Vangelis assisted the studio engineer at the mixing desk.

After a mix was completed onto a master tape, and before it could be dispatched to the film editor, the magnetic tape needed to be mastered for film on 35-mm sound film. Vangelis’ studio engineer would take the 4-track tape reels to CTS Studios at Wembley, London, where the audio would be transferred to sound-film format. This process resulted in a 35-mm film coated with magnetic oxide particles that contained the sound transfer of the music. This type of transfer is one generation down from the master tape, and it is intended to facilitate the film editing tasks. This provided a way to align sound to pictures using the sprocketed film printing machines, while at the same time maintaining a high-quality audio transfer on magnetic medium.

Afterwards, the 35-mm sound film was taken to the dubbing theatre at Pinewood Studios, where it was dubbed to film. Vangelis’ instructions, suggesting where to align the music to which film frame, were relayed to the resident dubbing mixing engineer, and the film’s editor Terry Rawlings. The dubbing sessions of Vangelis’ film score were carried out separately from the film’s other sound sessions, such as adding Foley, sound effects and post-sync dialogues. The music dubbing sessions first took place at at Pinewood Studios, but towards the end of the Blade Runner project the sessions were moved to a much smaller sound booth at Twickenham Film Studios. Vangelis visited the dubbing sessions a few times to watch the film scenes, both with and without music.

Once the synchronised soundtrack was ready to be committed to optical film print via a photochemical process, a magnetic recording of the composite soundtrack was copied onto 4-track tape. This composite soundtrack, called ‘Music and Effects’ (M&E) tape, contained both the music and sound effects but excluded the actors’ dialogues. The M&E tape would later be copied and sent to international film distributors that required the film’s dialogue to be dubbed into a non-English language. The tape enabled the final music with the sound effects to be available on high-quality magnetic tape and totally aligned with the film, only requiring the dialogue of the chosen foreign language to be added.

Film director Ridley Scott visited Vangelis at his studio in the evenings during post-production, and the visits were light-hearted and social. Ridley was able to listen to Vangelis performing his latest film compositions live as they watched the film on a video screen or played back some of the latest compositions that Vangelis had been working on.

Towards the end of the project, as the score and film editing for Blade Runner was finalised, any new final tweaks to the edits were re-sent to Vangelis’ studio. Vangelis would then reappraise every new film scene to see if it could be shortened or lengthened; or, as was often the case, he would compose new music. This ensured film scenes were given spontaneous compositions and retained a level of engagement, as Vangelis responded to the film’s moving images.

Vangelis finished Blade Runner’s musical score around April 1982. The film’s post-production and editing continued for a few more weeks before the film opened in UK cinemas on 9 September 1982.

Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner, with its thought-provoking storyline and its beautifully set-up scenes, invited Vangelis’ music to unfold into a spectrum of musical styles, from simple backdrop music to grand haunting themes. Some of Vangelis’ most imaginative music occurs when it takes a mutual coexistence with the visual fabric of the film, as his electronically driven score seems to have fused with the film’s exquisite imagery. At its most synergistic symbioses, there is a blurring of boundaries between what is sound and what is vision.

Vangelis describes his approach to composing for film as spontaneous and instinctive. Preferring to let his spontaneity react to the images and not letting his thoughts interfere with his inspiration, he acts as a participant in the film by letting his instincts react to the scene and letting his music be driven by his first impression of the images. For Vangelis, the music in Blade Runner was an integral and inseparable part of the film, as the film testifies to the power of the music.

Vangelis’ film score for Blade Runner

Music composed, arranged, performed

and produced by

VANGELIS

Saxophone on ‘Love Theme’ by

Dick Morrissey

Performer on ‘Tales of the Future’ by

Demis Roussos

Performer on ‘One More Kiss, Dear’ by

Don Percival

Lyrics by

Peter Skellern

Recorded in Wembley, London

Performer on ‘Dr Tyrell's Death’ by

The English Chamber Choir

Sound recording engineer

Raine Shine

Recorded at Nemo Studios, London

December 1981 to April 1982 (guesstimated)

Chief dubbing mixers

Graham V. Hartstone (Pinewood Film Studios)

Gerry Humphreys (Twickenham Film Studios)

Film editor

Terry Rawlings

Nemo Studios’ equipment, synthesisers, and instruments, 1982

Analogue Synthesis

Yamaha CS-80 •

Yamaha CS-40M •

Roland VP-330 VocoderPlus MK I •

Sequential Circuits Prophet 10 •

Roland Jupiter 4 •

Roland SH-09

Analogue Drum Machines

Roland CR-5000 CompuRhythm •

Simmons SDSV with drum pad suitcase

CV/Gate Controllers and Sequencers

Roland ProMars CompuPhonic •

Roland CSQ-600 •

Roland CSQ-100

Roland System-100

Moog MiniMoog

RSF Kobol Black Box

ARP Sequencer

Digital Sampling Synthesis

E-Mu Emulator •

LINN LM-1 drum computer (preset)

FM Synthesis

Yamaha GS-1 •

Recording and Mixing

Quad/Eight Pacifica ( 36 channel inline mixing desk) •

dbx 216 16-channel Type I noise reduction (multitrack tapes) •

dbx 158 8-channel Type I noise reduction (multitrack tapes) •

Dolby A-Type noise reduction (mixdown mastering) •

Lyrec TR 532 2-inch 24-track tape recorder •

Ampex ATR-100 quarter-inch 2-track master tape recorder •

Studer 4-track master tape recorder (hired) •

Reverbs and Delays

Lexicon 224 digital reverb •

Master Room spring reverb

Compressors and Equalisers

Klark Teknik DN-27 graphic equaliser

Klark Teknik DN-22 graphic equaliser

URei 1176-LN peak limiter

Microphones

AKG-414, Sennheiser, and Electro-Voice

Monitoring

Tannoy Dreadnought Monitors

BGW 750B amplifiers

• Indicates known or strongly suspected use on Blade Runner

Electro-Acoustical Keyboards

Fender Rhodes 88 suitcase piano •

Yamaha CP-80 piano •

Acoustic Keyboard

Steinway & Sons Concert Grand Piano •

Acoustic Instruments

20-inch circular saw blade

Bell trees

Crotales

Gamelan

Glockenspiel

3 hand-tuned Timpani

Koto - Japanese stringed instrument •

Standard drum kit

Symphonic gongs

Symphonic snare drum

Thunder sheet

Tubular bell

Vibraphone

Wind gong

Organ

Hammond B3

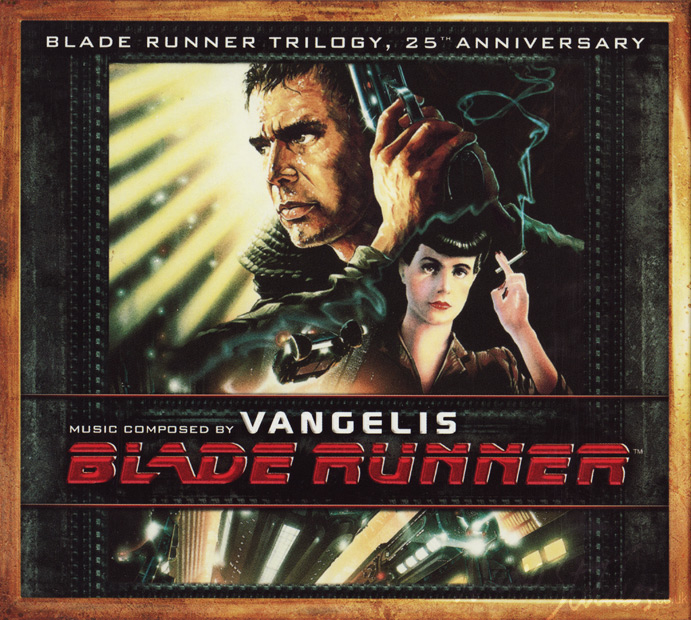

Vangelis - Blade Runner 3 CD music set

The Blade Runner Trilogy 3 CD set constitutes the official and most complete release of Vangelis' music from Blade Runner. It was released in 2007 to commemorate the 25th anniversary of the film's release. The release contains:

CD 1 features the original album as it first appeared in 1994, twelve years after the film was released.

CD 2 features additional music from the film, which did not appear on the original 1994 release.

CD 3 features an album of entirely new music by Vangelis to mark the 25th anniversary of Blade Runner.

External links to online music stores where this release can be obtained.

amazon.co.uk | amazon.com | amazon.co.jp

amazon.de | amazon.fr | amazon.it

iTunes

Other Features

PORTRAIT OF A RECORDING STUDIO

PORTRAIT OF A RECORDING STUDIO

A look at Vangelis’ Nemo Studios

SWEET NEMORIES - PHOTO SLIDESHOW

SWEET NEMORIES - PHOTO SLIDESHOW

Vangelis’ studio slideshow

A MUSICAL JOURNEY

A MUSICAL JOURNEY

Vangelis’ workography

MAIN WEBSITE

MAIN WEBSITE

Back to main site

Recommended viewings

On the Edge of Blade Runner, Mark Kermode, Channel-4, 2000.

Dangerous Days: Making Blade Runner, Charles de Lauzirika, Warner Home Video, 2007.

Blade Runner - The Final Cut, Ridley Scott, Warner Bros, 2007.

Recommended readings

Chariots’ One-Man Symphony, William Tuohy, Los Angeles Times, 3 April 1982.

Vangelis: Oscar-Winning Synthesist, Bob Doerschuk, Keyboard, August 1982.

Mechanic of Music, Andrew Duncan, Telegraph Sunday, November 1982.

Vangelis speaks, Dan Goldstein, Electronics & Music Maker, December 1984.

Vangelis: Career, Myth & Odyssey, Jean-Christophe Arion and Didier Leprêtre, Dreams, February/March 2002.

From the heart: The Power of Music, Michael Bond, New Scientist, 29 November 2003.

Future Noir, Paul M. Sammon, Orion Publishing, 2007.

VANGELIS’ Blade Runner film score

Copyright © 2024 nemostudios.co.uk